7. Concussion and whiplash

/My last post was pretty heavy, so I wanted to make sure I followed up with a post outlining the central causes of my headaches so people don’t think I’m as doomed as I sounded last week.

Throughout the long, arduous process of figuring out how to recover from my concussion, I had always believed that part of my issues were related to my neck. It certainly gave me doubts when doctors of all backgrounds told me it had nothing to do with my neck, but I could still never shake an intuitive feeling that it did.

The Clues

I thought this for a couple of reasons:

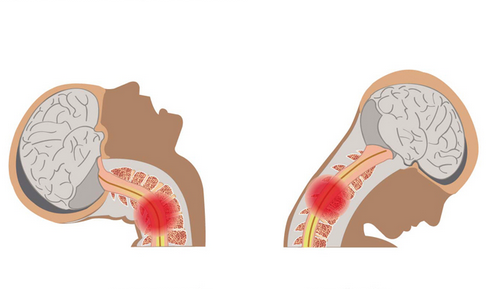

First, the way I was hit. I was hit from behind, which caused my head to forcefully and abruptly jerk backwards before propelling forward with the rest of my body. It was whiplash in its most obvious form.

Yet all of my pain and discomfort manifested entirely in my head as opposed to my neck. I had no neck pain, no obvious range of motion limitations, and no pain in the back of my head, which are all typical indicators of a neck-induced headache.

Despite this, however, there was one major clue that suggested my issues were in fact being generated from my neck.

Over time I realized there was a central driver of my headaches:

Gravity.

When I lie down, I get relief. When I am upright, the pain in my head increases. More specifically, when the muscles in my neck are not engaged, I get relief and when they are engaged, I feel pain.

It took some time to realize that it was actually the position of my body that was influencing my symptoms rather than the amount of cognitive rest I got. Initially I thought my symptoms would calm down when I wasn’t using my brain to think. I thought this, of course, because this is a typical pattern of a concussion. And it’s what my doctors told me would happen.

So while I was constantly thinking in terms of brain activity and its effect on my symptoms, I should have been considering the stress I was putting on my neck when holding it upright. My headaches always worsened with every bit of activity I subjected myself to in the same way that an ankle sprain would worsen if you kept running on it without giving it any real chance to heal.

The average head weighs around ten pounds and it’s your neck’s job to hold it upright. Let’s say you get eight hours of sleep a night and you stay upright the entire day. That’s sixteen straight hours that your neck muscles are working to hold up your ten-pound head. This is more or less what I did for a year and a half while I had significant structural damage to my neck.

When you think of it in this way, it’s no wonder that my symptoms got so bad over time; eventually leaving me bed-ridden. Yet neurologists were dumbfounded when I aced every cognitive test they could think of, and instead attributed all of my symptoms to anxiety.

Thankfully, in May of 2015, I finally found two doctors that were not only able to validate and clearly explain that the injury was related to my neck, but they knew how to appropriately treat it as well. I will spend considerable time writing about these doctors and the tremendous concussion program they have in Ann Arbor, Michigan, but for now I will detail how they helped me understand my injury.

The Migraneous Pattern

I learned that when a concussion occurs, it triggers a cascading pattern in the brain similar to a migraine. In response to this initiating event in the central nervous system (your brain), the peripheral nervous system (areas outside the brain) is activated to produce a pain response.

The brain itself is a numb structure, which means that the pain you experience in your head comes from the outer layers of the peripheral nervous system surrounding your brain. It is this outer system that does all of the hurting, which just so happens to have connections to the neck and feeds into the brainstem at the base of our skulls.

This is relevant to me because over time my peripheral nervous system (areas outside the brain) became the main driver of my symptoms. I was told that at some point in time, and they have no way of knowing exactly when, my concussion (the actual trauma to my brain) had healed.

What did not heal and what was never effectively addressed were the structural injuries to my neck, which is part of the peripheral nervous system.

My doctors explained this delay in my recovery like this:

Concussions excite your nervous system and place it in a hyperactive state, thereby producing headaches and other concussion-like symptoms. Yet although concussions are triggered by a mechanism inside the brain, symptoms can still be perpetuated by structural damage outside of the brain.

And this is exactly what happened to me; my brain has recovered but my nervous system is still hyperactive due to neck trauma. In other words, my symptoms are being driven from the "outside in" rather than the "inside out".

This was the first time I had heard any of this but it made so much sense to me. The brain and neck are so intimately connected and far too often the biomechanical issues of the neck are overlooked when it comes to evaluating concussions and concussion-like symptoms.

The Structural Damage

What this all means for me is that the nerves surrounding my head are hypersensitive and when my neck muscles are engaged, these nerves are irritated and begin sending referral pain signals to my head.

This hyperactivity has never had a chance to calm down because no one was able to pinpoint and treat the injuries to my neck until this past May, just shy of a year and a half since the damage first occurred.

The Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation doctor in Michigan, Dr. Miles Colwell, found a couple of issues with my neck, which were largely isolated to the upper right side of my neck.

this muscle, when damaged, can send referral pain the top of the head. I will discuss referral pain and trigger points in a later post.

The first thing he picked up on was that the Splenius Capitis muscle, which connects your skull to your neck, was torn in five places on the right side of my neck at the base of my skull. Whereas healthy muscle tissue is supposed to be smooth and supple, Dr. Colwell said the muscle at the base of my skull instead felt like thick, tight guitar strings.

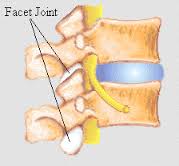

Along with this, he found a contusion at the facet joint connecting the C2 and C3 vertebrae, also on the right side of my neck.

Facet Joints connect vertebrae to one another and are highly innervated.

The damage to these areas caused significant overcompensation from the healthy musculature that bordered these areas. And the more the musculature tensed in its attempt to provide support for these unaddressed injuries, the more debilitating my headaches became, eventually becoming so severe that I couldn’t get out of bed.

My doctors’ plan for addressing all of this involves a combination of careful myofascial release work and physical therapy, stretching and strengthening exercises, and a series of isometric mobilizations. I was also prescribed a nerve-stabilizing medication to help break the nerve-firing pattern my body has fallen into. This plan would appropriately treat the injury as well as begin to down regulate my psycho, extremely hyperactive nervous system.

Re-Thinking Concussion Evaluation and Treatment

Neck trauma can attribute to a variety of concussion-like symptoms, both physical and cognitive. My neck injury perpetuated intense headaches, but cervical and sub-occipital restrictions can also produce symptoms such as dizziness, fogginess, visual tracking issues and more.

The problem with this statement, however, is that there is no meter or gauge to easily confirm it. We can only go off a doctor’s experience addressing neck issues and the results patients get from it.

What I can say from my experience is that once a qualified doctor identified and addressed my neck trauma, I began to see a reduction in the intensity of my headaches. And this is why I believe it’s so imperative that the biomechanical issues (i.e. neck trauma) associated with concussions are properly evaluated and treated.

If someone were able to diagnose and treat my neck injuries on day one, my life would be very, very different right now. It should not have taken me a year and a half to find the help I needed to get well, and this is the driving force for my blog.

The systems that are currently in place to treat concussions simply aren’t good enough, and I hope my story reflects the need for improvements across the board.